Intimate Partner Violence: Identification and Initial Response Clinical Audit

The Safer Families Centre has developed a clinical audit CPD activity for GPs on Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) Identification and Initial Response. The activity aims to provide a better understanding of IPV and how to identify and ask patients about it. GPs will also strengthen their capacity to identify barriers to asking about IPV and how to overcome those barriers. The activity also attracts up to 10 RACGP CPD hours in Measuring Outcomes for GPs.

The clinical audit has been designed to be easy to use and navigate and is fully accredited by the RACGP as a CPD audit activity.

There are two versions of the audit available.

-

Self-reflect on your own consultations and reflect on the strengths and areas where you could improve,

Analyse how intimate partner violence presents in general practice,

Identify the reasons why certain consultation prove to be difficult, and what can be altered to reduce the degree of difficulty, and

Refine your practice and improve patient outcomes from identifying and/or responding to/ addressing IPV.

-

After completing this audit activity, you should be able to:

Describe how IPB might present in general practice,

Identify possible cases of IPV in general practice,

Inquire sensitively about the possibility of IPV, and

Reflect on barriers to asking about IPV and identify how you may overcome them.

-

‘Intimate Partner Violence (IPV)’ also known as ‘Domestic Violence (DV)’ refers to any behaviour by an intimate partner (or ex-partner) that causes physical, sexual or psychological harm, including acts of physical violence, sexual coercion, psychological abuse and controlling behaviours.(1) It is a pattern of behaviour where one partner is usually exerting power and control over the other partner over time.

Figures from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare showed that one in six women and one in sixteen men have experienced sexual or physical assault from a current or former partner.(2) Around two thirds of the households where DV/IPV is occurring have children living in them.(3) Women are more likely than men to experience DV/IPV and to be injured as a result.(4) DV/IPV is the highest contributor to morbidity and mortality for Australian women of child-bearing age.(5) In Australia, a woman dies every nine days at the hands of their current or former partner.(2)

People experiencing DV/IPV access medical care for a wide range of health reasons more frequently than those who have not experienced abuse and are more likely to first tell a doctor or a nurse about the abuse before other professionals.(6) A full time GP is likely to have five women per week attending the clinic with underlying DV/IPV, yet most are not identified(7) as the majority of health practitioners do not ask about abuse, or they feel that patients do not want to disclose it to them.(8)

There are many barriers as to why practitioners may not address DV/IPV.(8) Some GPs do not see it as their role, fear offending the patient, feel they don’t have the skills, or, more importantly, enough time to provide an adequate response. Practitioners are often impeded by system barriers including presence of the partner or do not feel supported through a lack of training, referral or support services.(9)

It is important for GP’s and other health practitioners to reflect on their readiness to undertake this work, understand the complexities of DV/IPV in different populations and identify their own roles with individual patients.(10)

This Clinical Audit activity will focus on giving participants a better understanding of the indicators of DV/IPV and how to identify potential DV/IPV, and a better understanding of the barriers they have for asking about it and how to overcome these barriers.

Publications:

1. World Health Organization. Responding to intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women: WHO clinical and policy guidelines [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/85240

2. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia: continuing the national story 2019 [Internet]. Canberra; 2019 [cited 2020 May 11]. Available from: www.aihw.gov.au

3. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Personal safety, Australia. Canberra; 2017.

4. Webster K. A preventable burden: Measuring and addressing the prevalence and health impacts of intimate partner violence in Australian women: Key findings and future directions. Sydney; 2016 Nov.

5. Ayre J, Lum On M, Webster K, Gourley M, Moon L. Examination of the burden of disease of intimate partner violence against women in 2011: final report. Sydney; 2016.

6. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2018). Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia 2018 (Cat. no. FDV 2). Canberra: AIHW. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/domestic-violence/family-domestic-sexual-violence-in-australia-2018/contents/table-of-contents

7. Hegarty K, Andrews S, Tarzia L Transforming health settings to address gender-based violence in Australia. MEDICAL JOURNAL OF AUSTRALIA. 2022; 217(3): 159-166. doi:10.5694/mja2.51638

8. Tarzia, L., Cameron, J., Watson, J., Fiolet, R., Baloch, S., Robertson, R., Kyei-Onanjiri, M., McKibbin, G., Hegarty, K. (2021). Personal barriers to addressing intimate partner abuse: a qualitative meta-synthesis of healthcare practitioners’ experiences. BMC Health Services Research, 21(1), 567.

9. Hudspeth N, Cameron J, Baloch S, et al. Health practitioners’ perceptions of structural barriers to the identification of intimate partner abuse: a qualitative meta-synthesis. BMC Health Serv Res 2022; 22: 96.

10. Hegarty K, McKibbin G, Hameed M, et al. Health practitioners’ readiness to address domestic violence and abuse: a qualitative meta-synthesis. PLoS One 2020; 15: e0234067.

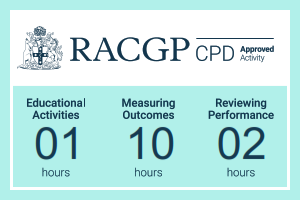

ACRRM CPD activity total 13 hours for the full audit- 1 hours Educational Activity (EA), 10 hours Measuring Outcomes (MO) and 2 hours Reviewing Performance (RP).

ACRRM CPD activity total 7 hours for the mini audit- 1 hours Educational Activity (EA) and 6 hours Measuring Outcomes (MO).

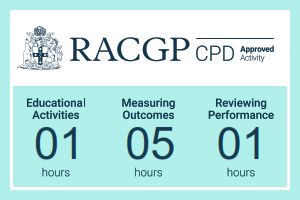

A mini audit that is comprised of 3 steps (approximately 7 hours to complete):

Step 1: Preparation & Planning

Step 2: Data collection

Step 3: Data analysis

A full audit that is comprised of 4 steps (approximately 13 hours to complete):

Step 1: Preparation & Planning

Step 2: Data collection

Step 3: Data analysis

Step 4: Repeat data collection and analysis